Heslop Murder 1891 Part 2 - The Trial

At

4 p.m., Monday March 14, 1892, Jack Bartram and his nephew, Jack Lottridge,

arrived at the Wentworth County Court House to formally enter their pleas to

the murder charges they faced.

Knowing that the prisoners would be

making an appearance, a reporter for the Hamilton Spectator was on hand to

describe the event:

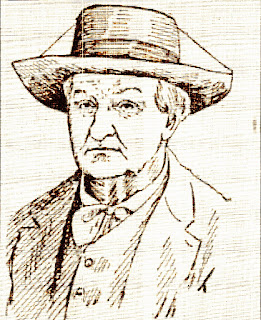

“Bartram was ushered in so quietly that

few people noticed him until he was seen sitting behind the bars. His hair is

quite silvery, and he looks like a man of fifty-five or sixty. He wears a short,

grey beard now, but his moustache is a reddish brown.

“If it was not for the alleged cancerous

eye, Bartram is rather benevolent and inoffensive in appearance. His right eye

is nearly closed, and seems to be almost blind, and he kept continually wiping

it with a handkerchief while in the dock. In fact, he kept furtively rubbing at

it, as if to make it appear as bad as possible.

“Shortly after Bartram’s arrival,

Lottridge was escorted in and paced at the opposite end of the dock, the two

prisoners being kept apart.

“Lottridge is not nearly so chirpy as he

was when brought up at the police court a few months ago. He looks thinner, as

if the strain was telling on him, and his face was very serious as he looked

about the court.”

When Court Clerk S. H. Ghent produced

the indictment, it was a different matter as regards Lottridge’s reaction:

“When interrogated, Lottridge replied

‘Not guilty’ in a firm voice, but his face quivered and he was evidently

somewhat excited, as he grasped the iron bars of the dock firmly.”

The trial itself began the next day at 2

p.m.. Just before that hours, the lawyers for the defence arrived at the court

house and had a hard time getting into the building:

“The corridors and stairways were

densely jammed, and several policemen had to make a way for the judge before he

could make his way in.

At 2 o’clock, Judge Rose ascended the

bench :

“Immediately after, the big doors were

opened, and the crowd came thronging in with great tumult, and took seats wherever

they could get places within the barrister’s rail.”

The process of jury selection was the

first matter before the court. Clerk Ghent instructed the prisoners that they

could challenge any of the men proposed for the jury:

“As each jury man stood up to be sworn,

the counsel of each side scrutinized him closely and consulted together, and

finally either accepted or rejected him.

“Among the rejected of the lawyers was

Thomas Reche, the genial manager of the Grand Opera House, who looked quite

disappointed, but he was one of many.

“Most young men were challenged and the

personnel of the jury was that of elderly men.”

The trial caused a sensation in

Hamilton. Every day, the court house seemed under siege as great crowds

gathered to witness the proceedings.

The police and court officials were hard

pressed to handle the situation. The Hamilton Herald reporter assigned to cover

the trial described their strategy as follows:

“On other days, the outer doors of the

building have been open to all who chose to enter and the efforts of the

constables have been directed to keeping the stairways and upper corridors

clear until the court begins work.

“But this morning, even the outer doors

were locked, and guarded by stalwart policemen, who scarcely could be persuaded

to open them for admission of those connected with the case, and others who had

a right to enter.

“The prisoners were brought in early,

and soon after them the jurors. Five minutes before the hour for starting,

Judge Rose arrived, the court was opened formally and the jurors answered to

their names. Meanwhile, a considerable number of ladies had found their way in,

and counsel for the crown, and for the defense were in their seats at the

table.

“During the few minutes between His

Lordship’s entrance and the calling of the first witness, the outer doors were

opened and the waiting crowd surged noisily in and up the stairs, making no end

of row as they found seats. Occasionally, a careless individual among them

would forget to remove his hat, and would bring down upon his devoted head the

wrath of one of the sheriff’s assistants.”

During the trial, the Toronto Globe sent

one of its reporters, Madge Merton, to Hamilton to cover the Heslop murder

trial from a woman’s point of view:

“All Hamilton is talking of the trial

and so what more was to be expected of a woman with an hour free than that she

should go to the court house, especially if she had been gravely assured by her

most particular cousin that there were ‘lots of ladies’ and ‘you really should

not miss it.’

“ ‘Step back!’ cried a big policeman to

a man who crowded forward. Then, seeing us, he added more kindly, ‘but there’s

a few seats left for the ladies.’

“ ‘To be sure, there were efforts to

maintain silence among the spectators, and an authoritative voice called

‘order’ occasionally, while a large white hand waved a warning towards the

noisy part but one could not help wishing that tones had the strong, persuasive

power of the well-known Mr. Henley at the Union station who makes known, with

such telling effect that all should be aboard for ‘Hamilton, London and

Suspension Bri-i-idge’ etc.”

The

day that Madge Merton listened to testimony at the Heslop trial, one of the

Indians was testifying:

“The

witness was an Indian, who looked as nervous as any Indian can while he wears a

look of stolidity that is the heritage of the self-torturing braves who were

his ancestors.

“His

face was calm. His voice, though husky with emotion, was yet well-sustained;

but he fidgeted on his feet and moved his hands restlessly. His eyes shifted

from the face of his questioner to that of the interpreter and occasionally the

sound of unintelligible words came up from the side of the box, and the witness

replied in Indian.”

The

Globe reporter took particular note of the behavior of the two prisoners during

the trial:

“Lottridge

‘s head barely showed above the railing of the dock. His figure seems short and

thick set. His forehead is low and his eyes grave. The muscles of his tawny

face were calm, and only once did I see him move. It was when he beckoned Mr.

Nesbitt to him and poured a cautious sentence or two from a mouth

well-sheltered by a brawny hand into a conveniently upturned ear.”

Bartram,

she wrote, was also very cool in the court room :

“His

face is pale. And his hair and whiskers are grey. One eye is much disfigured by

a growth, and the muscles of the right side of his face are restless. His hands

are slender and white and he had an odd trick of brushing down a mop of his

hair on his brow, and passing his fingers nervously over the bald top of his

head.

“He

gave the most perfect attention to the witness and, once or twice, he bent

forward, open-mouthed to listen.”

Madge

Merton was, of course, sympathetic to the hard work being done by the other newspaper

reporters covering the trial :

“The

newspaper men looked up and down and wrote hurriedly with one ear open and half

their brains at the service of Mr. Crerar and the Indian all the while.”

Not

a detail in the court room escaped Madge Merton’s observation :

“Sheriff

McKellar read the morning paper and glanced around the court now and again with

a benevolent and interested look.

“Judge

Rose sat with a meditative finger upon his brow. I could see only his profile.

It looked properly judicial and mentally alert.

“The

sunlight fell through the southern windows, and from them one could see the

mountain. It was draped with snow this morning, and the sun glided it, chasing

the shadows into the fissures and blackening the fir trees.”

After

all the testimony had been given, Crown Attorney Crerar summed up the evidence

for the prosecution in his address to the jury:

“He

asked the jury to believe that the family were acting in concert to provide an

alibi that the prisoner was in Cayuga, but the lawyers, probably thinking it untenable,

substituted the other alibi that Jack was at home, and they remembered by

another load of wood that was taken to Hamilton.

“Lottridge

told the detectives he wouldn’t know Douglas or Goosey if he saw them, but the

moment he saw Douglas in the Brantford jail, Sears tells us he rushed up and

spoke to him, telling him to keep his mouth shut about the murder as only four

of them knew about it, and nothing could be done to them.

“

‘Your responsibility, gentlemen, is no greater than your duty, and your duty is

imperative.’ ”

Judge

Rose, in charging the jury, cautioned them to consider the confessions of

Goosey and Douglas very carefully:

“

‘It would be interesting’ he said, ‘to have it known exactly how much the facts

were revealed by the newspapers and at the inquest, and what new facts are

detailed in the evidence of Goosey and Douglas that would tend to show that

these two men were actors in the crime.’ ”

During

Judge Rose’s charge to the jury, utter silence prevailed in the court room. As

the judge’s charge proceeded, the excitement rose:

“

‘If upon that evidence, you come to the conclusion as a finding of fact that

the prisoners, Bartram and Lottridge, were two of the four that went to Heslop’s

house and took part in that robbery and murder, then you will do your duty and

find them guilty.

“

‘But if, after considering the matter as I now direct, you are unable to

conclude or determine that the story told by these two men, Goosey and Douglas,

is a true story, then your mind has not come to a conclusion, and the prisoners

should be acquitted.’ ”

During

the early part of Judge Rose’s charge to the jury, Jack Bartram, already

confident of the strength of his defense, felt that the judge was directing the

jury to move for the prisoners’ acquittal.

However,

as Judge Rose continued, Bartram’s confidence was shaken:

“As

the judge warmed to his work and came down the home stretch of his admirable

charge, as he dealt sledgehammer blows at the fragile structure of the

prisoners’ defense, Bartram’s assumed indifference speedily vanished. Before

that charge was done, Bartram had swung his feet to the floor and with his

nervous hands grasping the bars of the dock, and his dilated eye fastened on

the speaker, he was listening to every word, while the beads of perspiration on

his forehead showed the intense excitement under which he labored.”

The

jury retired at 5:50 p.m., Thursday, March 25, 1892, The court was then

adjourned until 8 o’clock:

“From

the time the jury went out until after nine, the crowd outside increased to

nearly a thousand people. Inside, the people dozed or talked, the reporters

lounged about reading the papers or writing, in the anteroom s groups of

lawyers sat smoking and discussing the charge of Judge Rose, which was generally

considered to be told very heavily against the prisoners’ chances of acquittal.”

At

9:25 p.m. that evening, word was sent from the jury room that a verdict had

been reached:

“A

few minutes later, the constables ushered in the prisoners and placed them in

the dock. Old man Bartram was deathly white, and even Jack Lottridge’s dark

complexion showed an ashy hue.

“Lottridge

sat facing towards the door, by which the jurors were to enter, as if eager to

read the decision in their faces as they entered.”

At

9:45, Judge Rose entered the courtroom and a few minutes later, the jury was

led in:

“The

fact that they carried their coats and hats was an indication that a verdict

had been reached.

“

‘Gentlemen of the jury, have you agreed upon a verdict?’ ssked the clerk.

“Foreman

Steel stood up and said, in a low voice, ‘Not guilty.’

“The

most of the people could not hear it, but the fact was soon whispered abut and

the prisoners’ eyes glistened.

“Lottridge

was immediately arraigned on a charge of burglary, and Bartram was also

retained in custody on another bill. The crowd crushed around the dock to

congratulate them, and also to shake hands with their counsel.”

The

jury, it seems, had difficulty believing the confessions of the two Indians,

particular Douglas’ testimony. While there was strong evidence for conviction,

the conflicting testimony was also strong enough to give the prisoners the

benefit of a reasonable doubt as to their guilt.

Jack

Bartram was remanded to jail, while Lottridge was able to be freed on bail. When

Lottridge and his uncle parted, Batram wish his nephew well, and they shook

hands:

“The

parting was cordial. Lottridge wished Bartram good health and spirits during

the remaining eighteen or twenty months of his imprisonment on his months’

sentence for stealing cattle.”

Mrs.

Bartram came to visit her husband after the trial, accompanied by her son and

daughter, plus by Bartram’s two brothers, Henry and William Bartram of

Middleport:

“The

meeting between husband and wife was not marked by any particular display of

affection – no rushing into each other’s arms or anything of that sort. Mrs.

Bartram shook hands with her husband and said she was glad that he had been

acquitted of the awful charge.”

There

had been a total of 116 witnesses brought before the jury in the Heslop murder

trial :

“The

crown has already paid out $1,400 in witness fees and $341 for jury fees. The

whole cost of the jury panel was $854. It is roughly estimated that the cost of

trying to ferret out and punish the persons guilty of the Heslop murder has

been about $8,000. That estimate includes the inquest, detectives’ expenses,

and all other charges.”

Comments

Post a Comment