Heslop Murder 1891 Part 1 - Investigation and Arrests

The

day after John Heslop was murdered in his Ancaster Township home, the

provincial government assigned one of its detectives to take over the

investigation into the crime.

On his arrival in Hamilton, Detective William

Greer was described by a Spectator reporter as a young man “of very

uncommunicative disposition, leaving the reporter to “sigh for the oratorical

powers and dramatic appreciation of the value of facts for which some other

members of the provincial detective force are noted.”

Greer

was a good-looking young man, with rosy cheeks and a blonde moustache.

As

Greer refused to divulge the direction his investigation was taking, the press

and the public began to wonder if the detective was actually working hard

enough to solve the crime.

In

spite of substantial rewards offered by the provincial government, the county

council and the township council, there was no break in the case until nearly

eleven months after the shooting.

On

November 9, 1891, a headline in the Hamilton Spectator boldly asked “Is the

Murderer Caught?”

Until

the arrest of a suspect in the case, Detective Greer had been under mounting

criticism for his failure to solve the Heslop murder case: “While public opinion has been content to

let the tragedy pass away among the list of unexplained mysteries, the

machinery of the law has been quietly closing around the perpetrators of that

dastardly deed.”

Arrests

were made in Niagara Falls of two men. The names of the prisoners were Samuel

Gossie and George Douglas. A reporter had heard a rumour that the arrest of the

two men might be related to the Heslop murder.

At

first, Detective Greer denied the speculation and insisted that Gossie and

Douglas were only under arrest for stealing cattle from farms on the Onandaga

reserve.

On

December 8, 1891, another man, Jack Bartram, was arrested. Described as a

“white man, living at Middleport, near the Indian reserve, who bore a hard

reputation, Jack Bartram had been the terror of the vicinity for years.

As

soon as he was arrested, Bartam, reportedly drunk at the time, was quoted as

saying; ‘Look here now, you’ve got me solid, but if you will let me off the

charge of cattle-stealing, I will give you some good pointers about the fellows

who murdered old man Heslop last winter.’

“

‘I can’t let you off,’ replied arresting officer Adams, ‘you must come to

Brantford with me.’

“

‘Well,’ said Bartram, ‘when we get up there you tell them that I know who

killed the old man and will give the whole thing away if they will only let me

go.’

Later,

at the jail, Bartram refused to discuss anything to do with the Heslop.

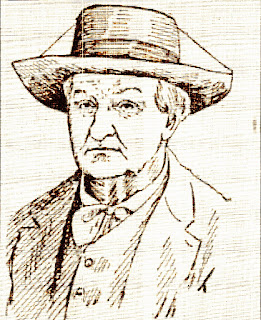

Jack

Bartram was about 54 years old, six feet tall, with grey hair and beard. His

right eye was swollen and enflamed, the result of a suspected cancerous tumor.

Bartram

had been arrested at his house, located a few miles south of Brantford:

“On

the left hand side of the village of Middleport, looking towards the east on

the opposite side of the road to the post office, stands Jack Bartram’s home.

It is a tumbledown-looking, ramshackle house of one storey. It has been neither

painted nor white-washed for ages, and is literally falling to pieces.

“The

house is built with its end towards and right close up to the sidewalk. The

chimney is on the center roof; there is a kitchen a foot or two less in height

at the rear, and beside windows in the side and end, there is a door in each of

these sections. Next to it in the same lot is an old barn tumbling to pieces,

while under the very window almost is a heap of manure.

“It

is easily the worst home in the village.”

The

Hamilton Times thoroughly investigated Jack Bartram’s past and in the edition

of the Weekly Times dated December 17, 1891, the following resume of Bartram’s

criminal past was published:

“About

twenty years ago, a gang of outlaws composed of Jack Bartram, Dave Poss, Sam

Lindsay, George Johnston (alias Shephard), Roge Hobson and a man named Knox

ruled the country around Middleport. The inhabitants lived in a state of

terror, while their property and chattels were in constant jeopardy.

“If

an attempt was made to bring the desperados to justice, the complainant would

find shortly afterwards that his cattle and horses had been killed or stolen,

and, in not a few circumstances, houses and barns were fired by this villainous

gang.

“After

this condition of things had existed for a brief period, the Bartram-Lindsay

gang, as it was called, expropriated whatever they chose without fear of being

brought to justice. They operated for a number of years and many of them were

reported to have accumulated considerable wealth.

“On

one occasion, the gang stole a flock of sheep, numbering more than one hundred,

from the reserve, drove them down through Copetown and onto Toronto where they

were sold

“An

East Indian woman named Brock lived, until a short time ago, a few miles from

Brantford on the Hamilton road. Her house was broken into one night by the gang

while looking for plunder. The brave woman jumped from her bed, seized a

shotgun and fired.

“The

robbers decamped, but the next morning the dead body of Poss was found a few

hundred yards from the house with his head riddled with shot. That was along

about ’74, but, in the next year, by the daring shrewdness of a man named Sol

Dean, the remainder of the gang were brought to bay and punished.

“

Dean, who was a veteran of Balaklava, went to live in Middleport, where he

joined the gang, at the same time being paid for his work by the authorities.

“The

gang held a secret meeting to which the new member was admitted, and it was

arranged to waylay and rob a wealthy citizen named Harbottle.

“Full

arrangements were made and the plot was carried out with some success. The

victim was thrown from his horse and robbed of $2,000.

“Dean

left the place quietly and gave full particulars to the authorities. Bartram,

Lindsay and Johnston (alias Sheppard), were arrested, tried and convicted.

Lindsay was sent to Kingston Penitentiary for twenty years, where he has since

died, and the others went to jail for shorter terms.

“This

had the effect of breaking up the notorious gang, and since that time, Bartram

has usually carried on his trepidations alone, though ona smaller scale, and

has eluded the very best of the county constables.”

Soon

after Bartram’s arrest, his son, who lived with his estranged wife in Michigan,

came to Brantford. Described in the Times as a “handsome young fellow (who)

does not resemble his father in the least,” the younger Bartram was ushered

into his father’s cell. He shook hands with his father, but not a word was

spoken :

“The

boy gazed hard at the prisoner from the time he came in until he went out, but

Jack Bartram seemed unconscious of his son’s presence, and stood there with his

usual hardened look.”

After

Bartram had been arrested, his nephew, a 28-year old half-breed Indian named

Jack Lottridge was placed under arrest while he was at the Commercial Hotel in

Brantford.

Lottridge

was not told the nature of the charges against him until Chief Vaughan read him

the warrant as the prisoner was being transferred from the police station to

the jail. When Lottridge realized that he was charged with murder, he

collapsed. After he recovered, he refused to say anything to the police, and

insisted on being put in the same cell as his uncle. His demand was denied.

During

the course of an interview with a reporter from the Brantford Expositor,

Detective Greer was quoted as saying:

“

‘This murder business was handed over to me two days after its occurrence. As

is usual on such occasions, I had a thousand and one clues, all of which I

carefully traced and exploded. In fact, I found that none of them would pan

out.

“

‘This is the latest tip we have had, and I have no doubt this is the gang with

the exception of Goosey.

“

‘ I got my first suspicions roused from the fact that there was a great number

of rough characters located in the vicinity of Ancaster. The crime was

performed in such a cool and dastardly manner that I had no doubt that it was

performed by men well-accustomed to the committal of crime.

“

I don’t mean to say that murder was the original intention of the men, but the

old gentleman was plucky, and had he not been so, probably there would have

been no murder.

“

‘ Both Goosey and Douglas were in the United Staes, and were kidnapped by the

ingenuity of the officers. I am not at liberty to say just now how that little

trick was worked.

“

‘They had only been on Canadian soil one day when they were captured. They were

induced to come across the line by perfectly legitimate means so far as I am

concerned, and as far as the American officers were concerned.

“

‘The Indian, Goosey, is about 25 years of age, nt 21 as you stated. He has been

in trouble before, but is merely held as a material witness.’ ”

Back

in Hamilton, a reporter for the Times interviewed Police Chief Hugh McKinnon

about Jack Bartram and his possible connection with the Heslop case :

“

‘I have known Bartram for 20 or 25 years, and the detectives know him well. He

is a hard man and generally has bad ones around him. His particular criminal

work has been larceny, robbery and house-breaking. His name was mentioned in

connection with the murder of Mr. Heslop within a few days after the affair,

and within two weeks a thorough investigation was made. At that time, the

conclusion arrived at was that Bartram was not the murderer. It was thought,

however, that he might possibly know something about it, and as it was known

that he could not leave the country because he was wanted in the United States

no attempt was made to arrest him.

“Bartram

has made Onandaga, Middleport, Hagersville and Caledonia his run for a long

time. Some considerable time ago, he was charged with cattle-stealing, but ran

away while the constables were looking for him. The grand jury found a true

bill against him and he was arrested on a bench warrant. From what I can hear,

there is little doubt that he will be convicted of cattle-stealing.”

The

Times reporter sensed that the chief was not very sure of Jack Bartram’s

participation in the Heslop murder :

“From

what the chief said it may be inferred that he has no strong ground for

believing that the real murderer has been arrested.”

The

Toronto Globe reporter covering the Heslop case was the first to tell the

provincial about Chief McKinnon’s misgivings regarding Bartram’s involvement

with the murder of the aged treasurer:

“Detective

Greer, when spoken to in regard to Chief McKinnon’s view regarding the affair,

was very indignant and remarked that the statement made by the chief to the

effect that the original information given the detective came from Hamilton was

wholly incorrect.

“

‘ The Hamilton men never were able,’ he said, ‘to get on anything until every

person else had it.’ ”

The

Globe reporter concluded that not only had the provincial detective

misunderstood McKinnon’s comments, he also had “allowed the green-eyed monster

to lay hands upon him.”

The

Hamilton Spectator, on December 11, 1891, published an indignant response to

the provincial detective’s actions :

“Detective

Greer talks too much. He fills up the Globe reporter with a lot of information

which, when investigated, is found to be based chiefly upon surmise. There is

reason to believe that the prominence which the young detective has gained over

this affair has swelled his head. His arrogance in taking all the credit to

himself has alienated Chief Vaughan and his staff who have done good work in

connection with the case and supplied much of the information upon which Greer

has taken action.”

On

December 10, 1891, Jack Lottridge was brought from Brantford to Hamilton to

await his trial in the palatial surroundings of the Wentworth County jail on

Barton street.

The

Hamilton Spectator reporter heard of Lottridge’s transfer to Hamilton, and

raced to the Stuart street station to meet the train :

“The

travellers eyed the handsome young detective and his prisoner curiously but few

of them knew that the man was one of the alleged Heslop murderers.

“When

Lottridge walked on the sidewalk to Stuart street, he was recognized by several

hackmen who called out, ‘Hello, Johnny.’ The prisoner seemed pleased at the

recognition and smilingly replied, ‘How are you boys?’ ”

Back

in Brantford, Jack Bartram was awaiting his trial on the cattle-stealing when

his wife, daughter and son arrived from Michigan to pay him a visit. Governor

Kitchen acceded to the family request to see his prisoner, and he personally

led the family to Bartram’s cell:

“They

found him as usual reading a pamphlet, and from which he did not withdraw his

attention when the heavy bolts were drawn back.

“When

the governor told him that his wife and little girl had called to see him, he

started up in astonishment. The child, who is 8 years of age, rushed to her

father, crying pitifully, and three her arms about his neck, while his wife, a

dignified-looking woman, looked on with freezing indifference.

“Twice

or three times, Jack said, ‘You need not be afraid, I can get out of this thing

alright.’ ”

As

the year 1891 was drawing to a close, there was a startling development in the

Heslop murder investigation. When the two Indians, Goosey and Douglas, who were

being held on charges of cattle-stealing, were reportedly told that Jack

Bartram was trying to implicate them in the murder, they decided to turn

Queen’s evidence and made a full confession.

The

two Indians had both been under intense pressure from the police to tell

everything they knew about the Heslop case. Goosey, it was widely rumored, had

been told that Bartram had sworn that Goosey was responsible for the actual

murder. When Goosey learned that he could receive immunity from prosecution, he

decided to reveal all he knew about the way that John Heslop met his death.

Bartram’s

lawyer was unimpressed with the impact that Goosey’s confession would make on

his client’s trial:

“

‘I take no stock whatever in that confession of Goosey’s. I shouldn’t be

surprised if the Indian Douglas made a similar confession. Such statements will

have no value unless they are corroborated by substantial evidence. You must

remember that a large reward is offered for the apprehension of the murderers,

and this reward the detectives and other officers are greedy for. You can’t

tell what pressure has been brought to bear on Goosey to extract this

confession from him. Why, you could buy up half the Indian reserve for the

amount of the reward offered. ‘ ”

When

Jack Douglas was told of Goosey’s confession, he too decided to tell all:

“

When he was in the cell at No. 3 Police station, he signified his desires to

confess and afterwards he repeated the story through an interpreter to the Police

Magistrate Cahill and Crown Attorney Crerar. Before making this statement, he

wanted to know what the proclamation meant. Under the proclamation, any of the

suspects, except the man who fired the fatal shot, are promised a pardon if

they confessed. Douglas shook like a leaf when he was making his statement.”

When

Jack Lottridge was told of the confessions of the two Indians, he refused to

crack:

“Lottridge

has wonderful nerve. Not a sign of nervousness did he betray anytime during the

examination. When a joke was cracked, he laughed with the others. The man is

not like the Indians. If he was in it, he intends to remain loyal to his uncle,

Jack Bartram.”

After

the sensational news of the confessions made by the two Indians, and in light

of Bartram’s and Lottridge’s refusals to admit to the crime, the editor of the

Brantford speculated about the possibility of racial factors influencing the

jury:

“The

fact that Goosey and Douglas, held for complicity in the Heslop case, have

confessed, while Bartram and Lottridge deny all knowledge of the crime, means

that the issue will be one of the word of two white men against that of two

Indians.”

After

being convicted of theft charges in Brantford, Jack Bartram was brought to

Hamilton to face the charge of murder.

A

reporter for the Hamilton Times was present at No. 3 Police station when the

handcuffed prisoner arrived in a rig, accompanied by a uniformed constable and

Provincil Detective Greer:

“Bartram

looked well. He was a little paler than when arrested and tried at Brantford,

his confinement probably being the cause of the change. He wore a white cotton

bandage over his right eye to hide the cancer which is said to threaten his

life.”

After

an hour was spent at the King William street station, the patrol wagon arrived

to transport the prisoner to the county jail on Barton street :

“There

is no jail in the province at which the officials are more careful than at the

Hamilton jail. The chances of a prisoner smuggling anything into his cell which

he should not are very small.

“A

very thorough of his (Bartram’s) clothing was made. A medium-sized hair pin was

the first thing found which was objected to. Bartram said he used it pick his

ear with and asked to be allowed to keep it.

“Smaller

things than hair pins have been instruments of self-destruction among

criminals, and the article of toilet was confiscated.

“When

the search of his boots was begun, Bartram was seen to be uneasy and to make a

motion that he evidently did not want seen.

“

‘What have you got there?’ was asked by the turnkey.

“

‘Nothing’ was the reply.

“But

the prisoner’s word would not be taken for it, and a search brought to light

the knife blade, which he had concealed in his boot. Bartram asked to be

allowed to keep it, but the cool request was laughed at.

“When

the officials were quite certain that nothing was hidden that Bartram should

not have, he was taken to a cell and locked up.”

Comments

Post a Comment